[ad_1]

During the last parliamentary sitting of 2022, New Zealand’s Labour-led government introduced legislation to drastically restructure the management of water infrastructure. The “Three Waters Reform” will take the running of wastewater, stormwater and drinking water out of the hands of 67 local councils and turn them over to four new regional Water Services Entities (WSEs).

The government claims that this centralisation will enable investment in the badly rundown water systems that have been neglected for decades. In 2021, for example, Wellington Water found that 31 percent of the capital city’s drinking water pipes were in a poor or very poor condition. Across the country, one third of wastewater treatment plants are in need of upgrades, and one in five people do not have tap water that is safe to drink.

Despite the restructure, however, Labour has refused to allocate the funding required to fix the crisis—estimated at $120 to $185 billion over the next three decades. Successive Labour and National Party governments have overseen decades of under-investment in water infrastructure, along with other vital services, in order to satisfy demands for tax cuts for big business.

Moreover, the new WSEs are being structured to make ‘cost recovery’ a key part of their operations. More user-pays mechanisms will be devised, with the burden falling disproportionately on working people. At present, only Auckland residents are charged for water use, but according to the New Zealand Herald, this system is now likely to be rolled out nationwide.

The most contentious element of the Three Waters legislation, however, is that it gives Māori tribes “co-governance” of water assets. The four WSEs will be directed by “Regional Representative Groups,” half controlled by elected council representatives and half controlled by unelected tribal representatives.

Although the Labour government claims that it will never privatise water assets, the indigenous tribes, known as iwi, are essentially private businesses, with significant economic and political power. The NZ Māori Council estimates that the “Māorieconomy,” now worth $60 to $70 billion, will grow to $100 billion within 10 years. Māori businesses own 50 percent of New Zealand’s fishing quota and have significant assets in dairy, beef, kiwifruit, forestry, honey, tourism and commercial property.

The National Iwi Chairs Forum, which represents this corporate layer, says the “co-governance” measure is to ensure that the Crown meets its obligations as a “Treaty partner.” This refers to the Treaty of Waitangi, signed between a group of tribal chiefs and the representatives of the British Empire in 1840. The treaty made false promises that the British would respect Māori sovereignty over their land. By the end of the century, however, following the bitter 1845–1872 New Zealand Wars, most land had been confiscated by the colonial power.

The Treaty has since the mid-1980s been elevated to the status of the country’s founding document, supposedly to address the historical crimes of colonisation. In fact, under a “Treaty settlements” process, tribes received multi-million dollar payments from the state, which they have used to establish lucrative business operations through the exploitation of workers of all races. A privileged layer has been created, consisting of Māori entrepreneurs, academics, lawyers, politicians and state sector leaders, dedicated to the defence of the profit system.

The growth of Māori capitalism has not done anything to improve the social distress facing the majority of Māori people, who make up 16 percent of the population and remain among the most oppressed sections of the working class. On every measure of social and economic wellbeing, including health, housing, education, income and wealth, Māori remain highly disadvantaged.

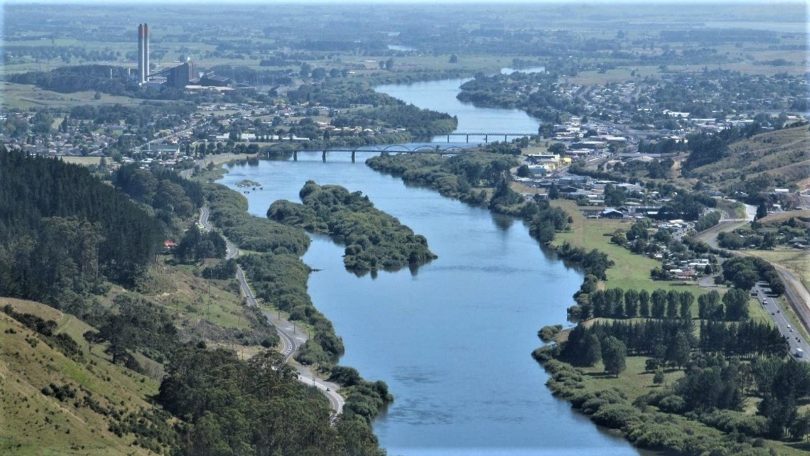

Denouncing opposition to Three Waters, Waikato-Tainui tribal chairperson Tukoroirangi Morgan—a former MP in the right-wing, anti-immigrant NZ First Party—declared: “I don’t know which world they belong to, this is 2022 Aotearoa New Zealand, this is about partnership.” The Waikato-Tainui group of tribes received over $170 million in Treaty settlements in the 1990s, and since 2010 it has been co-managing the Waikato River, which supplies a large amount of Auckland’s water.

Labour’s local government minister Nanaia Mahuta has presented the Waikato River Authority (WRA) as a model for what “co-governance” of water will look like. The WRA distributes approximately $6 million per year to entities, including tribal corporations and other businesses, mainly for environmental-related projects.

Under the Three Waters structure, however, far larger sums of money and vast water resources will be at the disposal of the WSEs. The government’s claims that these entities—largely controlled by private interests—will serve the needs of working people, are an out and out fraud. The WSEs will increase the opportunities for private businesses, including those with tribal connections, to profit from water infrastructure-related contracts.

The government is pushing ahead with a much broader “co-governance” agenda in several different policy areas that serves definite class purposes. Public services are increasingly being devolved to tribal businesses, including schools, social welfare and a new Māori Health Authority, which will deliver services exclusively “by Māori, for Māori.” Most local government bodies now have Māori wards where only people on the Māori parliamentary electoral roll can vote for representatives.

As it prepares for an election later this year amid intensifying class tensions, the Ardern government is appealing for support from layers of the bourgeoisie and upper middle class, who are seeking to advance their own privileges and wealth, even as social conditions for the vast majority continue to worsen. At the same time, Labour’s relentless promotion of race-based identity politics is intended to obscure its escalating assault on the entire working class, and to sow divisions based on race.

Labour’s support among workers, Māori and non-Māori alike, is rapidly falling. The government and Reserve Bank exploited the COVID pandemic to hand over tens of billions of dollars to private banks and corporations, leading to soaring social inequality, rampant inflation, along with thousands of preventable deaths from COVID-19 in 2022. The corporate elite intends to resolve the worsening economic crisis by driving down real wages and increasing unemployment.

There is also widespread public opposition to Three Waters. A majority of 88,000 public submissions to a parliamentary select committee opposed the restructure, with many saying it would lead to a loss of local control over water infrastructure.

The conservative National Party, and especially its far-right ally the ACT Party, are exploiting the opposition for political gain, while seeking to steer it in the most reactionary direction. Labour’s use of identity politics to justify further enriching the Māori elite has played directly into the hands of ACT, NZ First and other forces on the extreme right, which are stoking racism by falsely claiming that the Māori population as a whole is being given “privileged” status.

ACT leader David Seymour, for instance, denounces the “co-governance” of water infrastructure, not because it gives greater power to private corporations, but based on the claim that it allows “some people to have more influence than others based on their ethnicity.”

National and ACT have a long record of supporting privatisation, and ACT has put forward its own plan for private companies (including those with tribal links) to profit from water infrastructure. It advocates the use of “Public-Private Partnerships to attract investment from financial entities such as KiwiSaver funds, ACC, iwi investment funds, etc.”

On the other hand, the Māori Party, which represents Māori business interests in parliament, voted against the Three Waters legislation because “co-governance” did not go far enough. Co-leader Rawiri Waititi declared that “we [i.e. Māori] own the water, and that hasn’t been recognised in that particular bill.” Water ownership has been a longstanding goal of some tribal leaders.

The Māori Party was in power with National and ACT from 2008–17, but failed to be re-elected in 2017. The party returned in 2020 with co-leader Waititi calling for a “tiriti [Treaty]-centric Aotearoa” that would include a separate Māori parliament, so the majority doesn’t “rule over Māori.”

Among Labour’s increasingly desperate pseudo-left supporters, all opponents of Three Waters are lumped in with ACT and National and denounced as “racist.” The Daily Blog proclaims: “Our systems of power and control are all white, our dominant culture is white, our benefitting from colonialism is white, our purposeful laws aimed at taking more Māori land were white, our confiscations are white, our dominant narrative is white.”

This is entirely false. It is not “white society” that is responsible for the oppression of indigenous people, but the capitalist profit system. “Co-governance” is another effort to subordinate Māori workers to the tribal elite and to block a unified fight against the social crisis and a turn to socialism.

The Socialist Equality Group in New Zealand completely rejects the divisive racial politics promoted by the government and opposition parties alike in the toxic “debate” over Three Waters. Our opposition to the Labour government’s legislation is based on the socialist principle that private corporations profiting from water—the most vital of all natural resources—represents an attack on the fundamental rights of the working class, regardless of whether the beneficiaries are indigenous or non-indigenous companies.

The ruling class program of never-ending austerity, privatisations and the running down of public infrastructure can only be defeated by a movement of working people, of all ethnic and national backgrounds, to put an end to capitalism and to reorganise society along socialist lines. This includes nationalising all water infrastructure and placing it under the democratic control of the working class.

[ad_2]

Source link