[ad_1]

Despite its manufacturing capability, India, unlike other Asian countries, has failed to integrate into global value chains (GVCs). In this post, Karishma Banga discusses the nature of India’s GVC integration, primarily through forward participation; the sectors that fuel productive linkages; and the factors that have caused low integration – lack of well-developed, labour-intensive industries, large domestic market, labour market rigidities and low FDI. Finally, she recommends strategies to maximise gains for domestic firms integrating into GVCs.

The Covid-19 pandemic has put the spotlight back on global value chains (GVCs) as a driver of economic growth, industrial exports, and job creation. GVC trade differs from traditional trade, with the former involving intensive firm-to-firm interactions, characterised by contracting and specialised products and investment (Antras 2016). Economies with advanced technologies and high wages tend to offshore manufacturing stages of the value chain to nearby developing countries with low wages, leading to creation of regional supply chains (Baldwin 2006). One such regional supply chain is ‘Factory Asia’1. Despite its proximity to Factory Asia, and its manufacturing capability in several sectors, India has failed to integrate into GVCs (Baldwin 2011, Sen and Srivastava 2011, Athukorala 2019).

Nature of India’s GVC participation

India’s GVC participation is significantly lower than China, Vietnam, Korea and other Southeast Asian countries. Network products – for which GVCs are the dominant mode of production – such as electronics, computers, telecommunication equipment and vehicles, account for only 10% of India’s total merchandise exports (as compared to about 50% of the exports of China, Japan and Korea) (Veeramani and Dhir 2019).

Data from the Trade in Value Added (TiVA) database demonstrates that India links into GVCs mainly through forward participation (domestic value added (DVA) in exports of intermediate goods, as a share of gross exports) rather than backward participation2 (foreign value added (FVA) as a share of gross exports). This indicates its relatively higher engagement in upstream production activities3

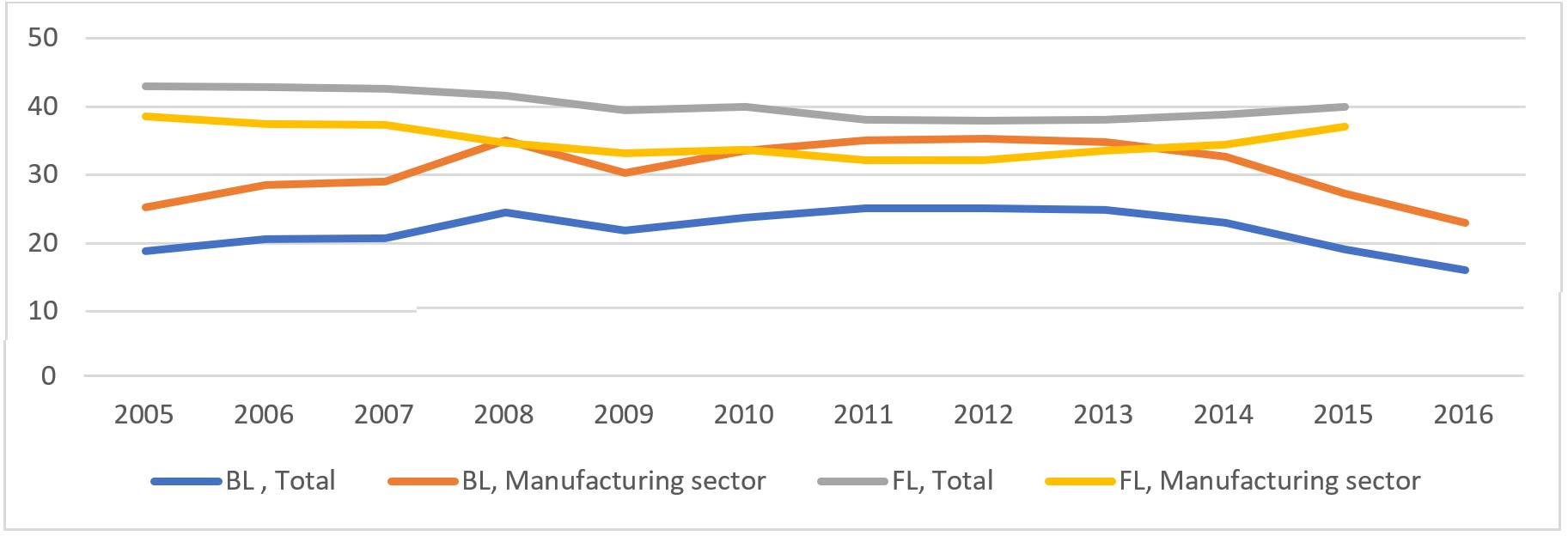

The largest share of India’s forward linkages is made up of renting machinery and equipment, followed by chemicals, coke and petroleum, basic and fabricated metals, textiles, and agriculture products (Mitra et al. 2020). Forward linkages in the manufacturing sector have been on the rise since 2012, while backward linkages have declined from 35% in 2012 to 23% in 2016 (Figure 1). Just six sectors account for nearly 60% of India’s manufacturing GVC exports – coke and petroleum (18.3% of GVC exports), renting of machinery (14.9%), chemicals (11.2%), basic and fabricated metals (8.6%), and transport equipment (6.3%) (Mitra et al. 2020).

Figure 1. India’s GVC participation linkages as a percentage of gross exports

Source: TiVA (2018).

Notes: i) Forward linkages = DVA in exports of intermediate goods (as a share of gross exports). ii) Backward linkages = FVA in gross exports (as a share of gross exports)

![]()

Why did India miss the GVC boat?

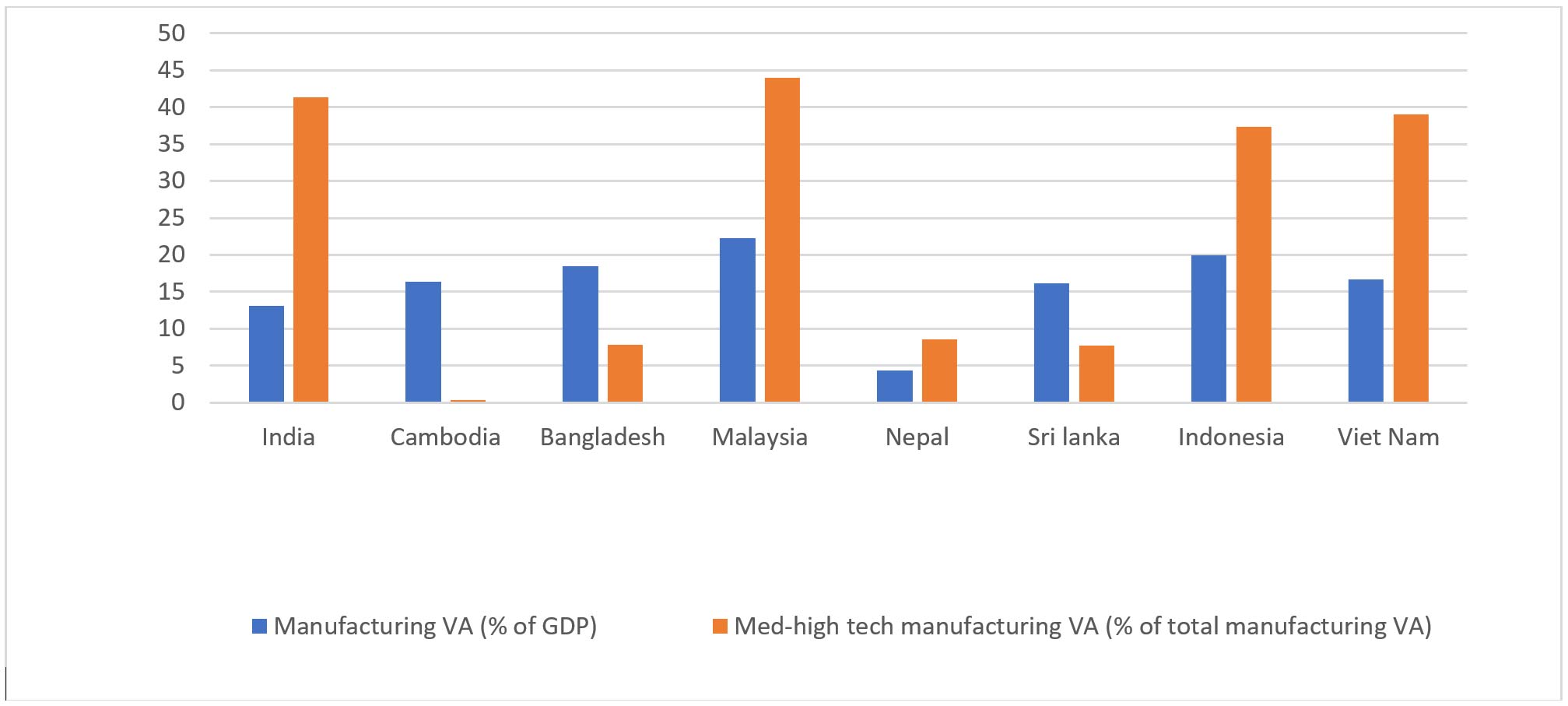

Unlike East Asia, India missed an important stage of promoting labour-intensive industries during its industrialisation. In 2020, the manufacturing value added share of India’s GDP was only 13%, much lower than other Asian economies (Figure 2). Despite having comparative advantages in unskilled labour-intensive manufacturing activities, India’s commodity composition of exports is biased towards capital- and skill-intensive products (Veeramani, 2019). India’s manufacturing GVC trade, both in terms of backward and forward linkages, has also gradually shifted from the Global North to countries in the Global South (Banga 2021).

Figure 2. Value added by manufacturing as a share of total GDP for Asian countries in 2020

Source: World Development Indicators

Note: Medium and high tech manufacturing includes industries in which producers of goods incur relatively high expenditure on research and development. The two taken together indicate the share of labour-intensive manufacturing in the country.

![]()

Higher absolute and relative labour market rigidities are known to deter foreign investment and lead to reduced GVC spill overs (Javorcik and Spatareanu 2005). In labour-intensive production, India’s archaic labour laws have created exit barriers, disincentivising large firms from choosing labour-intensive activities and technologies (Krueger 2010). Stringent labour market regulations have further resulted in a slow growth of employment in the manufacturing sector and labour market frictions, which have in turn led to the employment of inefficient labour (Panagariya 2008, Gupta and Kumar 2012).

Another reason for India’s low integration in labour-intensive chains (such as those of garments manufacturing) is the large size of the domestic market. In the presence of high export standards and strict delivery pressures, Indian garments firms find it easier to supply to the domestic market, and to neighbouring countries and the Middle East, which have lower quality standards compared to the US and EU (Ray 2019). Moreover, India’s forward participation is higher than backward participation in the textile, wearing apparel and leather value chain (Figure 3), indicating that Indian firms tend to link into the garments value chain at the lower end, exporting yarn and woven fabrics of cotton and of silk. This has been further confirmed using product-level analysis (see Gupta 2015).

Figure 3. Linkages in the textile, wearing apparel and leather GVC

A third contributing factor to India’s low GVC participation is its inability to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) into the manufacturing sector, and subsequent weak links with lead firms (Hoda and Rai 2018, Ray and Miglani 2020). Empirical evidence suggests that openness to FDI is positively associated with backward GVC participation. Other Asian economies, such Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Cambodia experienced growth in both FDI stock and GVC exports at more than 10% annually between 2010 and 2017, while India’s GVC participation witnessed a significant decline in the same period (Mitra et al. 2020).

A large part of Bangladesh’s success in the textile and apparel value chain lies in its successful lock-in of inward FDI from multinational corporations (MNCs), which relocated production units to Bangladesh to take advantage of the abundance of low-cost labour. FDI in the textile sector in Bangladesh also led to the growth of new domestic suppliers of buttons, zippers and fabrics, which increased the competitiveness of Bangladeshi textiles globally (Kee 2015).

Can Indian firms benefit from increasing GVC participation?

Manufacturing suppliers in emerging economies like India can benefit by exporting and importing through GVCs. The exposure to foreign competition and demands of international buyers can create new incentives for Indian firms to innovate, while firms can also learn from the technology and knowledge embedded in capital imports. Simultaneously engaging in both activities further unlocks cost complementarities (Wagner 2012).

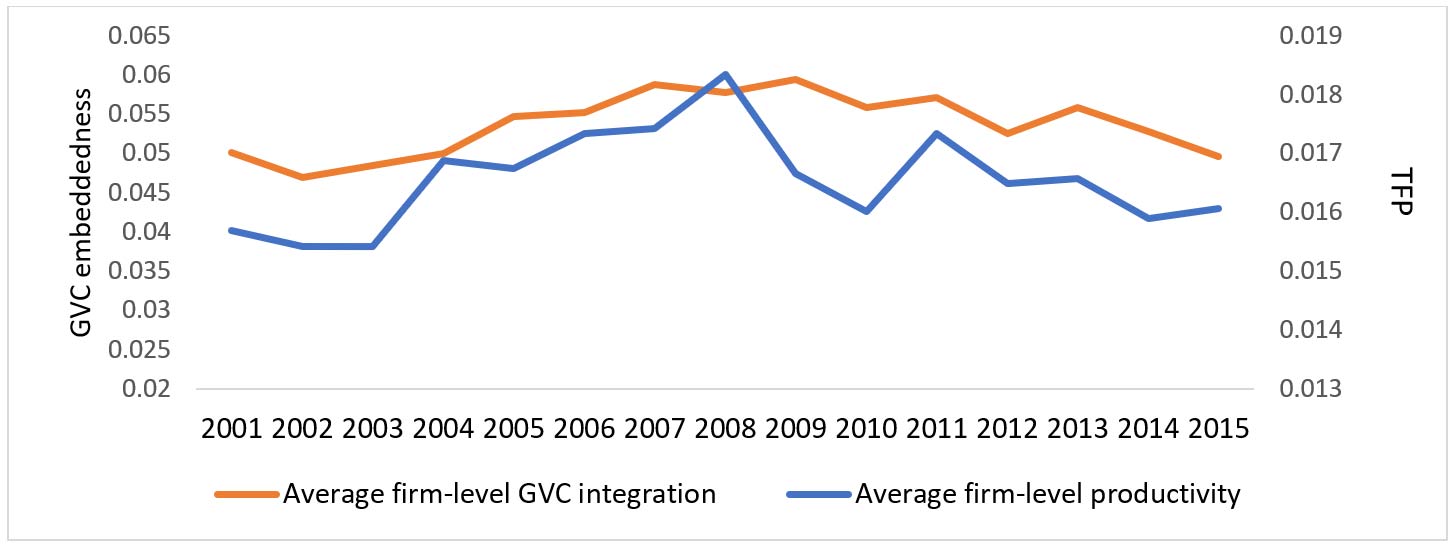

Firm-level GVC integration, captured by vertical specialisation4, has followed a similar path to that of firm-level total factor productivity (TFP) in India over the period 2001-2015. In Figure 4, we observe that between 2001 and 2008, both the average level of GVC integration and firm productivity increased. However, because of the financial crisis in 2008, there was a decline in average GVC integration and a fall in average productivity of Indian firms in the period 2008-2010, both of which recovered between 2010-2011 but thereafter continued to decline in the period 2011-2014.

Figure 4. Evolution of firm-level TFP and GVC embeddedness in Indian manufacturing

Source: Banga (2022a)

![]()

Heterogenous productivity gains from GVC linkages

Empirical evidence from the Indian manufacturing sector suggests that Indian firms in GVCs have a productivity premium of 13 to 22% relative to non-GVC firms, with the productivity premium from GVC linkages being higher in the automotive, electronics and IT industries, compared to textiles and chemicals (Manghnani et al. 2021). Examining the causal relationship between GVC participation and total factor productivity, in a recent study (Banga 2022a), I find that participating in a GVC and increasing GVC embeddedness boosts manufacturing firm productivity in India. Moreover, GVC linkages are evidenced to increase gross exports, domestic value-added and employment in India (Veeramani and Dhir 2022).

However, the gains from linking are not homogenous: both productivity gains and product sophistication gains are higher for Indian GVC firms that invest in digital capabilities and skilled labour (Banga 2022a, 2022b). Increasing backward linkages have had a negative impact on employment growth in Indian industries, while forward linkages have been found to have no significant impact (Banga 2016).

Conclusion: Industrial, FDI and trade policy recommendations for job creation

The time for leveraging GVCs for economic growth in India is now: at a time when the Covid-19 pandemic and US-China tensions have led to a wave of MNC relocations away from China, several policy initiatives are being rolled out by the Government of India to revitalise the manufacturing sector and to increase FDI. The subsequent realignment of GVCs could create new opportunities for India’s manufacturing sector (Baldwin and Tomiura 2020), particularly in sectors of ‘textiles, wearing apparel, leather and related products’ and ‘chemicals and non-metallic mineral products’ industries, where India could be an alternative to China when it comes to imports for the US (Bagaria 2021).

The discussion needs to shift from questions about how India can link into GVCs, to how India can leverage GVCs for economic growth and job creation. There is an urgent need to reorient India’s trade specialisation towards labour-intensive sectors, but this would require a targetted approach, based on traditional sectors and sectors with high participation in GVCs (Veeramani and Aerath 2020).

In capital-intensive sectors, where India has good GVC linkages (such as electronics and hardware) there is a need to promote exports and diversify into activities of assembling of final or network products (Athukorala 2014, Arora and Siddiqui 2020), and specialise in low-skill labour-intensive stages of production. Domestic firms in these sectors need to be incentivised to undertake research and development (R&D) activities, while foreign-invested firms in such sectors need to be incentivised to create more backward linkages within the domestic economy. The domestic integration of manufacturing GVC firms, specifically with the domestic technology/digital sector can facilitate large-scale employment gains in a fast-digitalising economy (Rodrik 2018).

India’s efforts to increase participation in free trade agreements (FTAs) have failed to attract export-oriented FDI from GVC lead firms, and have ultimately benefitted MNCs (Francis and Kallummal 2021). For example, deep and non-strategic trade liberalisation, combined with a liberal FDI policy regime, led to increasing import dependence in India’s electronics sector (Francis and Kallummal 2021). There is a need to develop a coherent industrial policy that aims at increasing DVA within the economy, creating links between the foreign firms and domestic suppliers, and facilitating technological upgrading and spillovers from FDI. A more targetted approach is also needed; the impact of FDI on productivity of an acquired Indian firm is higher when the FDI is from developed countries, particularly from USA or Europe, but spillovers on productivity from vertical forward linkages are higher when the FDI is from Asian countries (Goldar and Banga 2020).

A related point of action is to facilitate the ‘servicification’ of Indian manufacturing– services such as R&D, design services, branding and retail etc. play an essential role in manufacturing GVCs. While India lags other major economies in terms of the services content of its manufacturing exports, the increased use of services input can positively and significantly boost firm-level export intensity5 (Golder et al. 2017) and also sustain their survival in GVCs (Reddy and Sasidharan 2022). Offering support to firms through incentives and subsidies in deploying digital services can significantly increase manufacturing export competitiveness (Banga and Banga 2020).

Lastly, India needs to reorient its trade policy, with emphasis on developing its own GVCs. A potential pathway through which India can accomplish this is by leveraging its growing trade with partners in the Global South to establish its own GVCs, through outward FDI joint ventures that can supply intermediate inputs at competitive rates.

This post is the sixth in a six-part series on ‘The good jobs challenge in India’.

Notes:

- Factory Asia comprises of Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, China, South Korea, Taiwan and Japan (Baldwin 2011).

- Forward participation of a country refers to producing and shipping raw materials and intermediate inputs (for example, yarn) for further processing and exporting by other countries (fabric), while backward participation refers to using imported intermediate inputs ( imported fabrics) to produce goods that are exported (apparels).

- Upstream production refers to all the activities needed to gather the materials required to create a product. This will include raw material processing, for example, drilling and exploration in the oil industry. It is farthest from the end consumer. Downstream production, on the other hand, are activities that help the end-product get produced and distributed.

- Vertical specialisation occurs when a country relies on imports of intermediate goods and services to produce a good it later exports.

- The use of services, for example, can raise the total factor productivity of manufacturing firms, which can in turn lead to improved export performance of firms.

Further Reading

- Antras, P (2016), Global Production: Firms, Contracts and Trade Structure, Princeton University Press.

- Arora, Kashika and Areej Aftab Siddiqui (2020), “Technology Exports and Global Value Chain Linkages: A Comparative Sectoral Study of India”, The Indian Economic Journal, 68(1): 8-28.

- Athukorala, PC (2014), Global Production Sharing and Trade Patterns in East Asia. The Oxford Handbook of the Economics of the Pacific Rim.

- Athukorala, Prema-chandra (2019), “Joining global production networks: Experience and prospects of India”, Asian Economic Policy Review, 14(1): 123-143.

- Bagaria, Nidhi (2021), “Analysing opportunities for India in global value chains in post COVID-19 era”, Foreign Trade Review, 57(3).

- Baldwin, R (2006), ‘Globalisation: The Great Unbundling (S)’, Economic Council of Finland. Available here.

- Baldwin, R (2011), ‘Trade and industrialization after globalization’s 2nd unbundling: How building and joining a supply chain are different and why it matters’, NBER Working Paper 17716.

- Baldwin, R and E Tomiura (2020), ‘Thinking ahead about the trade impact of COVID-19’, in R Baldwin and B Weber di Mauro (eds.), Economics in the Time of COVID-19.

- Banga, Karishma (2016), “Impact of global value chains on employment in India”, Journal of Economic Integration, 31(3): 631-673.

- Banga, K (2021), ‘India’s manufacturing and services value-chains are shifting South; A curse or a blessing?’, UNU-WIDER Blog, July.

- Banga, Karishma (2022a), “Impact of global value chains on total factor productivity: The case of Indian manufacturing”, Review of Development Economics, 26(2): 704-735.

- Banga, Karishma (2022b), “Digital technologies and product upgrading in global value chains: Empirical evidence from Indian manufacturing firms”, The European Journal of Development Research, 34(1): 77-102.

- Banga, R and K Banga (2020), ‘Digitalization and India’s losing export competitiveness’, in SC Aggarwal, DK Das and R Banga (eds.), Accelerators of India’s Growth—Industry, Trade and Employment.

- Francis, S and M Kallummal (2021), ‘Indian Electronics Industry’s FDI-Led GVC Engagement: Theoretical and Policy Insights from a Firm-Level Analysis’ in S Mani and CG Iyer (eds.), India’s Economy and Society.

- Goldar, B and K Banga (2020), ‘Country origin of foreign direct investment in Indian manufacturing and its impact on productivity of domestic firms’, in NS Siddharthan and K Narayanan (eds.), FDI, Technology and Innovation.

- Goldar, Bishwanath, Rashmi Banga and Karishma Banga (2017), “India’s linkages into global value chains: The role of imported services”, India Policy Forum, 14(1): 107-172. Available here.

- Gupta, N (2015), ‘India’s Textiles and Clothing Industry in Global Value Chains and its Linkages with other Asian Countries’, Centre for WTO Studies Working Paper.

- Gupta, P and U Kumar (2012), ‘Performance of Indian Manufacturing in the Post-Reform Period’, in C Ghate (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Indian Economy.

- Hoda, A and D Rai (2018), ‘Trade and investment barriers affecting international production networks in India’, in J Menon and TN Srinivasan (eds.), Integrating South and East Asia: Economics of Regional Cooperation and Development.

- Javorcik, Beata and Mariana Spatareanu (2005), “Do foreign investors care about labor market regulations?”, Review of World Economics, 141(3): 375-403.

- Kee, Hiau Looi (2015), “Local intermediate inputs and the shared supplier spillovers of foreign direct investment”, Journal of Development Economics, 112: 56-71.

- Krueger, AO (2010), ‘India’s trade with the world: Retrospect and prospect’, in S Acharya and R Mohan (eds.), India’s Economy: Performance and Challenges.

- Manghnani, R, B Meyer, S Saez and E van Der Marel (2021), ‘Firm Performance, Participation in Global Value Chains and Service Inputs’, Policy Research Working Paper 9814, World Bank Group.

- Mitra, S, AS Gupta and A Sanganeria (2020), ‘Drivers and Benefits of Enhancing Participation in Global Value Chains: Lessons for India’, South Asia Working Paper Series No. 79, Asian Development Bank. Available here.

- Panagariya, A (2008), India: The Emerging Giant, Oxford University Press.

- Ray, S (2019), ‘What explains India’s poor performance in garments exports: evidence from five clusters?’, Working Paper 376, ICRIER.

- Ray, S and S Miglani (2018), Global value chains and the missing links: Cases from Indian industry, Routledge India.

- Reddy, Ketan and Subash Sasidharan (2022), “Servicification and global value chain survival: Firm‐level evidence from India”, Australian Economic Papers.

- Rodrik, D (2018), ‘New technologies, global value chains, and developing economies’, NBER Working Paper 25164

- Sen, R and S Srivastava (2011), ‘Integrating into Asia’s international production networks: Challenges and prospects for India’, in W Anukoonwattaka and M Mikic (eds.), India: A New Player in Asian Production Networks? Studies in Trade and Investment 75.

- Veeramani, C and L Aerath (2020), ‘India’s merchandise exports in a comparative Asian perspective’, in SC Aggarwal, DK Das and R Banga (eds.), Accelerators of India’s Growth—Industry, Trade and Employment.

- Veeramani, C and G Dhir (2019), ‘Dynamics and determinants of fragmentation trade: Asian countries in comparative and long-term perspective’, Working Paper No. 2019-040, Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research.

- Veeramani, Choorikkad and Garima Dhir (2022), “Do developing countries gain by participating in global value chains? Evidence from India”, Review of World Economics: 1-32.

- Veeramani, C (2019), “Fragmentation trade and vertical specialisation: How does South Asia compare with China”, Journal of Asian Economic Integration, 1(1): 97-128.

- Wagner, Joachim (2012), “International Trade and Firm Performance”, Review of World Economics, 148(2): 235-267. Available here.

[ad_2]

Source link