[ad_1]

Most people experience the Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos as a blur of half-conversations, chattering panels about a mind-boggling range of topics, the occasional memorable soundbite, shaking hands on at least one great deal or agreement, a memorable talk by a world leader in the Congress Hall, and staying upright on the icy roads and pavements. For me, the most lasting image was a moment during a high-profile panel discussion on Leading the Charge Through Earth’s New Normal that took place in the most prestigious venue, the Congress Hall.

One of the many “nature pics” that floated across the giant screen behind the panel of speakers was of a Sumatran orangutan peering somewhat puzzled at the several hundred humans earnestly chattering away about the destruction of the planet and what needs to be done to save the life-support systems humans depend on.

I was mesmerised by the irony of the moment: balanced on her jungle perch, it would never occur to this orangutan to cut away the branch she was sitting on for fear of falling to the ground way below. And yet, this is exactly what we humans have done: for the sake of profit for a few, we have all but destroyed the life-support systems we depend on. No wonder those intelligent eyes seem so curious, so puzzled and so, so sad.

The WEF Annual Meeting is many things at the same time. On the surface, it is four days of panel discussions on a mind-boggling range of topics, from the global economic crisis, to the future of democracy, to technological change, demographic trends, health and the war in Ukraine.

Following on from the Financial Times’ anointment of the word “polycrisis” as the keyword for 2022, many moderators opened their panels with a reference to the polycrisis — gone were the neoliberal certainties of yesteryears.

There is no place for long in-depth talks at WEF: panels comprise speakers who are given five minutes each to respond to a key opening question from the moderator, and then it’s up to the moderator to weave together a narrative from the diverse threads that emerge. Below the casual appearance of a dialogue, it is all carefully choreographed.

Richard Quest aptly described the shared Alpine language used to weave together the tapestry as “Davosian”. Those who have mastered the art of the well-selected Davosian soundbite are the ones that shape the narrative. The rest take note and go home to cities around the world rehearsing their favourite Davosian phrases.

But other things also happen: speaking to the author of the strategy adopted by the WEF founders back in the day, the WEF has succeeded in becoming a global magnet for the elites because it is “where you come to be with others so that you can feel good about yourself, to have a conversation that fundamentally changes how you see a rapidly changing world, and to do at least one good deal”.

There are many who attend WEF just for the meetings: they attend sessions where they are panel speakers, but the rest of the time is spent reinforcing networks or having meetings with potential new partners in the Strategic Partners Lounge.

Often set up in advance, the WEF makes possible several in-person meetings in a day with people from very different geographical locations that would otherwise require travel over many weeks. Boasting at WEF is about subtly revealing which of the Swiss glitzy dinners you got invited to by one of the notable Jedi Knights of the global economy. It used to be about your place in the pecking order of the Royal Courts of a bygone imperial age, but in today’s world, it’s about which dinners at Davos you attended and where you sat in relation to the “head table”.

Around the inner core of WEF, there is an outer ring of events that are not part of the formal programme — they are hosted by a bewildering range of organisations, from banks to governments, to NGOs and consulting firms. Many of these events are where initiatives and reports are launched, enabling sponsors (some of whom are not even official delegates at the Annual Meeting) to create the impression that their reports were “launched at WEF”. Like at all such events (eg, the annual COP meetings, the annual meetings of the World Bank/IMF, etc), organisers ride on the convening power and branding of the main event.

When people say “we launched our report at the WEF”, it usually means they launched their report in a hotel conference room filled by members of their own network, somewhere nearby. When I was asked last year, “Are you attending COP?”, that means swanning around the events that encircle the actual COP — a meeting of government delegations that comprise a minority of the total number who “attend the COP”. Global governance has become a set of staged performances by a moving circus of inner-circle actors and outer-circle hangers-on, and it starts off in the snow at Davos each year.

Back to the polycrisis

Returning to the polycrisis, the plenary session that the Sumatran orangutan briefly surveyed started with a truly awesome presentation by professors Johan Rockström and Joyeeta Gupta. Synthesising the cutting edge of the most well-funded global science in the world, the first 10 minutes of the session were a spectacular visual representation of the fragility of our planet and how social justice is unachievable when planetary systems are collapsing.

“We are taking risks with the future of civilisation on Earth,” Rockström almost shouted. “We are degrading the life support systems we all depend on.”

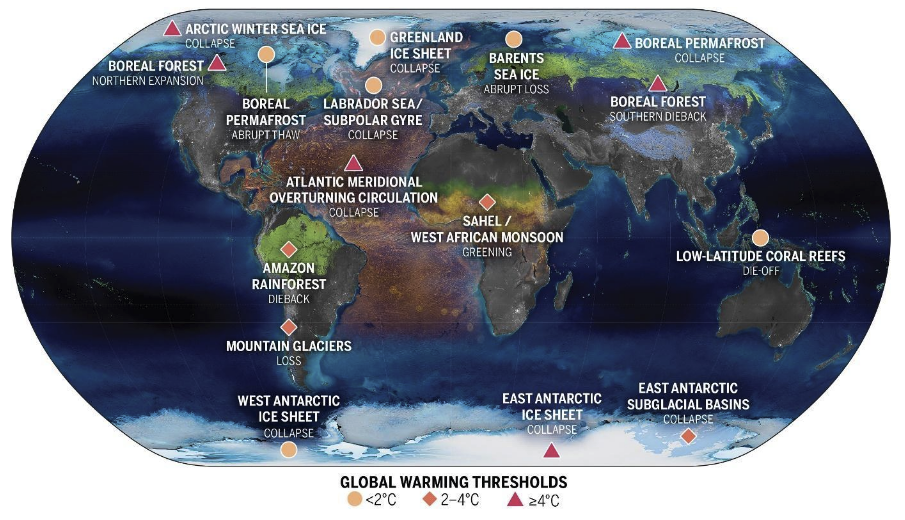

The professors proceeded to describe the 16 tipping elements of the global climate ecosystem — if conditions change to such an extent that any one of these elements tips into functioning differently, that could cascade across the system, triggering tipping points elsewhere in the system in ways that cannot be predicted.

The result would be a self-perpetuating and unstoppable reversal of the conditions that have made it possible for human civilisation to thrive over the past 15,000 years. If the current global warming rate of ~1.1 degrees rises to ~1.5 degrees, these tipping points could be triggered with highly unpredictable consequences. Nine of the 16 tipping points are close to tipping over. As warming continues, more and more parts of the planet become uninhabitable for humans. There is a safe and just corridor that needs to be protected by reversing global warming, but we have already breached the boundaries of this corridor.

This heart-stopping presentation was followed by contributions from Al Gore, Andrew Forrest (CEO of Fortescue Metals Group, Australia), Fawn Sharp (president of the National Congress of American Indians), Gustavo Francisco Petro Urrego (president of Colombia), Marc Benioff (CEO of Salesforce) and Roshni Nadar Malhotra (chairperson of HCL Tech, India).

For Benioff, Forrest and Gore, the message was simple: we must and can achieve Net Zero by 2050, preferably by 2030. All the technologies exist to make this happen. Forrest’s company has budgeted $6.2-billion to reconfigure his metals company to achieve Net Zero by 2030. For Fawn Sharp, the solutions are not technocratic: “What we do to our planet, we do to ourselves.”

Gore declared: “We are not winning — emissions are still going up. And what do I tell young people about solutions when the leader of the World Bank is a climate denier, and an oil company executive has been appointed the COP president?” The climate agenda has been hijacked by big oil, he lamented.

The newly elected left-wing president of Colombia had clearly not bothered to master Davosian: “Can capitalism overcome the climate crisis it helped to create?” he asked. He wondered whether “decarbonised capitalism” was achievable when the world economy is driven exclusively by profit.

As a footnote: sadly, I never came across anyone from the South African delegation at this event — if only one of the Cabinet Ministers present could have seen the Rockström-Gupta presentation.

Searching for positive tipping points

To counterbalance the negative tipping points I went in search of positive tipping points. I attended most of the many sessions on the energy transition, including the one on the just transition where I was a speaker on a panel. I learned nothing new, other than to notice that Africa was completely absent from these discussions — mostly white male panellists from the Global North.

I had to venture beyond the security area to an outer-ring session called The Breakthrough Effect: How to Trigger a Cascade of Tipping Points to Accelerate the Net Zero Transition. Hosted by SystemIQ (a consultancy), the University of Exeter and the Bezos Earth Fund, the narrative was compelling.

Twelve positive tipping points were identified, each of which could trigger a cascade of ripple effects that could accelerate the transition. These included renewable energy, light-duty battery-powered electric vehicles, heavy-duty battery- or hydrogen-powered electric vehicles, sustainable building materials and heating, fertiliser made from green ammonia (made from green hydrogen), green steel (because the energy inputs are green), shipping powered by green ammonia, green aviation fuels (eg, hydrogen), food and agriculture (new vegetable-based meat substitutes and regenerative farming), low carbon cement, and green chemical production. When taken together, if one or more of these tipped into production and consumption at scale, the effects would be transformative.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

The energy transition panels did not seem to go beyond normative calls to decarbonise by accelerating the adoption of renewables. The geopolitical implications of the energy transition seem to go unnoticed: nearly all the best wind and solar resources are in the Global South, most of the big biodiversity resources needed for adaptation are in the Global South, and the biggest mineral and metal resource pools needed to produce the renewable energy and storage infrastructures are in the Global South (in particular, rare earths, copper, steel, lithium and cement). And the large bulk of the capital needed to make it happen is (outside of China) in the Global North.

Unsurprising, then, that the panels on the energy transition were dominated by speakers from Global North institutions. My argument in my panel on Enabling an Equitable Transition was that the global financial system is not fit-for-purpose. With the financial assets of the mainly Global North-based financial institutions at 628% of GDP in 2020 (according to the FSB), until the rules of finance are changed, the acceleration of investments needed to scale up the positive tipping points will not materialise. The Colombian Minister of Environment, Susana Muhamad (a former student of mine) who was a co-panellist in the session, talked about the need for “fiscal space” to invest in the just transition.

A session that hit the spot

And so I went in search of panels from which I could learn more about the global dynamics of finance and the potential for the rebuilding of the manufacturing sector as rising production costs in China start making manufacturing viable in many regions around the world. The session on The Role of Finance in a Recovery was most instructive. Panellists included Adena Friedman (chair and CEO of Nasdaq), François Villeroy de Galhau (governor of the Bank of France), Michael Miebach (CEO of Mastercard) and Roelof Botha (managing partner of Sequoia Capital, and South African).

Unlike the sessions I attended where economists spouted generalities that had nothing to do with the real world of finance (because most don’t really understand finance, strangely enough), this session hit the spot. All more or less agreed that unlike three months ago, there are signs that the world economy might just avoid tipping into a global recession. But a polycrisis means uncertainties are an everyday reality.

At the centre of the discussion are inflation and interest rates, and the shared deep desire to return to “normal interest rates” of around 2%. This can only happen when inflationary pressures are under control (more or less achieved in the US, not in Europe — yet), and deflationary threats have been counteracted by unconventional interventions such as quantitative easing (QE) in the wake of the 2007/9 financial crisis.

And so the whizzy dialogue begins. Most agree that despite inflation, unemployment is not rising, and consumer spending remains robust but consumers are changing their spending patterns with fewer luxuries and more basics — no sign of recession from a consumer perspective. For venture capital funds, inflation does not affect their business. But if central banks panic and push interest rates too far, that would trigger a recession and affect small businesses.

There is disagreement about interest rates: some think they have peaked, others not. The big bogey in the room is the return of the Chinese consumer as Chinese growth picks up after a year of growth rates slower than the global average for the first time in 40 years — this could drive up consumption and spur inflation, which could trigger more interest rates. But interest rates are not about finance, but about inflation.

Over the last decade, central banks have developed a wider range of instruments — not just interest rates to bring down inflation when needed, but also the exercise of macro-prudential authority and QE to counteract deflation. The financial crisis was a banking crisis, and now the banks are well-regulated.

The number one worry now is not banking, but non-banking financial institutions — that is, the ones that central bankers do not control. They are responsible for the rise of crypto, for instance. The tendency towards crisis now lies in an overheated non-bank sector and crypto. The debate now is not about the regulation of crypto or not, but about the regulation or prohibition of crypto.

But some disagreed with this negative take on crypto. A total of $1-trillion of value was lost in the crypto crash of 2022, but it did not trigger a systemic crisis. Crypto is driven by specialist players, and banks are stepping back. Crypto can only become mainstream as a store of value when that market is regulated. Only then will banks step in. Crypto is about unbacked assets becoming mainstream but depends on regulation.

The value of crypto depends on whether there are enough people who believe it has value, thus it becomes a store of value — a system of mutual beliefs, and it could therefore work. Like gold — if everyone believed crypto has value, it will become a mainstream store of value.

It was clear to me that there was complete consensus that regulation could help create a new monetary architecture — like all money over the course of modern history, until the state steps in to make the rules, provide security and take its cut, crypto will remain marginal as a store of value for the few true believers.

A master of Davosian

In a different session on the role of development finance, the global development finance guru, Lord Nicholas Stern, presided. Drawing from his recent report, his starting point was the estimate that $4-trillion are needed per annum to realise the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Of this, $2.4-trillion per annum are required for climate mitigation and adaptation.

Nothing less will be adequate, he argued, if we want to address the “serial catastrophes” that we now face globally and locally. To achieve this level of annual investment, the 570 Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) around the world are key players, in particular the World Bank.

There is a widespread view at Davos that the World Bank has still not figured out how to play its role. Hence the call by US Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen to overhaul the multilateral development banking system.

As far as Stern is concerned, DFIs need to increase their annual investments by a factor of five, and then leverage co-funding on a 1:8 ratio. This is how to effect the redirection of capital away from financial assets into real-world needs. This is what he calls the “New Growth Story”. His total mastery of Davosian is a spectacle to behold — in a few perfectly articulated soundbites, delivered with the aplomb of an English lord, he shifts the entire room.

And so, as so often happens in financial discussions, it’s all about values, shared beliefs, trust and interminable speculations about unknowable futures. Money binds us together into mutually dependent communities because we believe that it reflects the value of whatever we are buying and selling in the real present and the imagined future.

In reality, money flows in ways that reproduce the futures preferred by the elites who write the rules. When investors extend credit, they create the new money that borrowers use to engage in economic activities that happen in the (unknowable) future that must generate the returns required to repay the lender.

But what matters here is who decides who receives the credit, on what basis, to create what kind of future, for the benefit of whom?

For Stern, the New Growth Story is about investing in a future for human civilisation. But for this, a new global agreement is required — like the Bretton Woods agreement at the end of the Second World War that framed the Growth Story that followed that particular catastrophe, will the Bridgetown Initiative (announced at COP27) provide the basis for the New Growth Story that is needed to mitigate our current catastrophe?

The return of manufacturing

During Davos week, The Economist ran a feature on the “return of manufacturing” — the number of companies which relocated their manufacturing operations back to their home base doubled in 2022 compared to 2021. I sat next to the CEO of the Industrial Development Corporation at a session called The Return of Manufacturing — we both share an obsession with the developmental potential of manufacturing. Panellists included Bandar Alkhorayef (minister of industry and mineral resources in Saudi Arabia), Gretchen Whitmer (governor of Michigan, US), Jacqueline Poh (MD of Singapore Economic Development Board), Michel Doukeris (CEO of Anheuser-Busch) and Roland Busch (CEO of Siemens).

Busch was by far the most interesting. Repeating the public statements of Siemens in recent times, he described the pre-Covid manufacturing paradigm as being about optimising labour costs, with no concern about the cost of resources, no concern about CO2 footprints, no geopolitical uncertainties and it was “one-way manufacturing” — take resources out the ground, and make things and do not worry about the waste. Then Covid came, and supply chains were disrupted.

The post-Covid paradigm is that low labour costs are no longer the focus (read: therefore, a China location is not essential), design for a low carbon footprint is essential, the use and reuse of resources is a better way, and therefore a desire for circularity.

Using digital technologies, fully design upfront, ie, build a “digital twin”, a kind of real-life prototype. Then build the finished product, getting it right the first time. This is followed by simulation and optimisation across many different locations. This increases productivity by 20%, reduces CO2 and ensures resource efficiency. It is a manufacturing model that relies on resource efficiency, not cheap labour, to make profits.

Siemens has a presence in 190 countries. Because optimising on low labour costs is no longer the focus, localisation becomes possible in locales where shorter, more strategic and locally coordinated value chains can be established — this is what industrial clustering looks like.

By combining the real and digital world to build the prototypes in the hi-tech centralised Siemens labs, simulation and optimisation can be replicated across many localities where the appropriate networks and clustering can occur. This makes it possible to fully understand the resource, carbon and labour implications of a given product. The big industry of the future is circularity and recycling.

Without suggesting Siemens operationalises in practice what the CEO envisages, it is nevertheless a narrative with many far-reaching implications, especially for African economies. If labour costs are not an issue, then China ceases to be the dominant locational player. If resources and carbon matter, then high labour costs are justifiable in locations where resource efficiencies and carbon mitigation are possible.

This cancels out locations supplied by high-carbon energy and where recycling waste is logistically impossible. Clustering shorter-distance value chains that connect suppliers with manufacturing is preferred, rather than depending on long-distance sources of resources and skills.

This opens up huge opportunities for South Africa. I was pleased that the CEO of the Industrial Development Corporation was listening to this. He heard that the Saudis have spotted the gap, and adopted an Industrial Strategy in October 2022 that effectively sets up Saudi Arabia as the ideal location for operationalising this new manufacturing paradigm. Michigan is doing exactly the same, and Singapore is retooling its large manufacturing base to align with the new requirements for low-carbon and resource-efficient infrastructures.

Global economic outlook: End of an era?

I would have liked to end off with a reflection on the session on the future of democracy. But it was a damp squib — all about the technocracies of election management, social media, systems of governance, etc. Nothing about the political economy of democracy, in particular, trends that suggest that capitalism may no longer need democracy in order to thrive (think Donald Trump).

So it is worth ending off with a reflection on the very last plenary session, entitled Global Economic Outlook: End of an Era? Ending a WEF with this question is telling — bring on the uncertainties of the polycrisis, goodbye to the certainties of the neoliberal era. Or maybe I misinterpreted the question…

The panellists were Bruno le Maire (French minister of economy, finance and industrial and digital sovereignty), Christine Lagarde (president of the European Central Bank), Kristalina Georgieva (MD of the IMF), Haruhiko Kuroda (governor of the Bank of Japan), and Lawrence Summers (president emeritus of Harvard University).

For Georgieva, things are less bad than we thought a few months ago, but that does not mean things are good. Yes, inflation is no longer rising fast, Chinese growth is recovering, consumer spending is up and labour markets are holding, but “be careful about being too optimistic”, she said.

Summers was more direct: populists are losing elections, Europe is not frozen (thus avoiding inflationary gas price hikes), inflation has decelerated and China has changed its politics. He warned central banks to stay the course — “keep focused on inflation”, he growled.

But he was worried: the poor are paying the highest price for structural reforms, global integration could cause local disintegration, technology can make a huge difference but policy mistakes could scupper the potential, debt is alarmingly high in many countries, and there are no signs that anyone has found a way to reallocate large amounts of capital from the Global North to the Global South.

A big topic of discussion at Davos was the implications of the Inflation Reduction Act in the US. This is a $336-billion stimulus for climate change mitigation and adaptation. That could, in turn, leverage up to $1-trillion in co-funding for climate action. Europe is scrambling to figure out how to match that. For Summers, a subsidy war between the US and Europe could be a good thing because it will catalyse innovation on both sides of the Atlantic.

Lagarde, however, in a thinly veiled warning, argued that fiscal policy needs to be more focused and better deployed, otherwise monetary policy will be under pressure to come to the rescue (again). Another worry for her is new growth in China (and she could have added Japan) that will push up energy prices, which will be inflationary globally.

For Le Maire, market-driven globalisation is over. Post-Covid, globalisation is politically driven. The biggest threats are world war (with Ukraine being the start), fragmentation of global powers (China versus the US, or the US versus Europe versus Japan), exclusion of China from global growth, and climate change.

“It is not USA first, or Europe first, or China first, it is climate first,” he thundered.

For him, climate change is by far our biggest challenge.

In short, Davos has come face-to-face with uncertainty. From polycrisis to the end of an era, the post-Covid world looks disconcertingly unpredictable and even unsafe. I doubt many made their way down the mountain in the snow feeling all that good about themselves.

Yes, they certainly heard things that changed their understanding of our fast-changing world, and surely many made some good deals. But I cannot but wonder whether the WEF is the creation of a bygone era. I have my doubts about whether it can retain its magnetic pull in a world that desperately needs new ideas, new paradigms and a much greater sense of urgency. It will probably ossify as it enlarges its staff and finds meaning by rolling out global programmes that it believes make a difference.

But I would not be surprised if, in the relatively near future, a rival space emerges that is more fit for purpose. When I look into the eyes of that orangutan from the Sumatran jungle, I see a deeper call on us to do better — much, much better. DM

![]()

[ad_2]

Source link