[ad_1]

DULUTH — Grain shipments through the Port of Duluth-Superior are lagging.

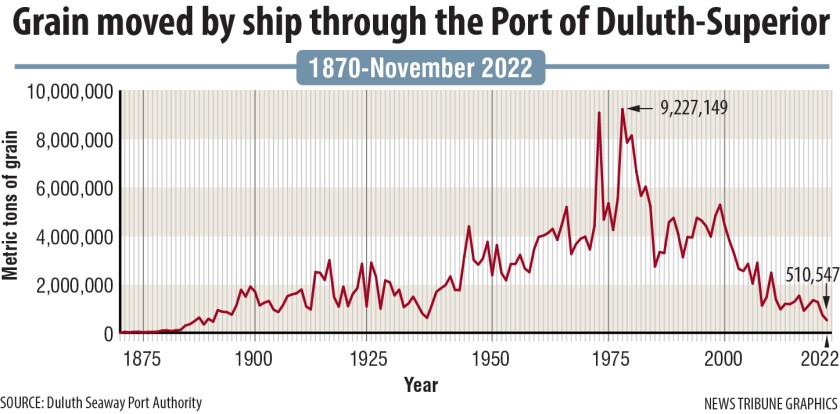

Through November, 510,547 metric tons of grain had moved through the port on ships so far this season, setting it up to be the lowest or second-lowest season since 1890, according

to historical tonnage figures dating back more than 150 years.

Gary Meader / Duluth News Tribune

Exports of grain by ship have declined for decades, down from a high of 9.2 million metric tons in 1978. Soybeans now go by rail to the West Coast, for example, and the geographic area where grains were harvested before being sent to the port for transport has shrunk,

among other factors.

But a unique set of circumstances have caused the 2022 decline.

Daniel Rust, associate professor of transportation and logistics management at the University of Wisconsin-Superior, said fewer ocean-going ships, or “salties,” coming into the port means less grain leaving the port.

“It’s oftentimes the case that grain outbound is a backhaul. There will be some other commodity coming in like wind energy components, (or) something else — that’s the reason for the vessel to come all the way to Duluth-Superior — and then they don’t want to go out empty. So they pick up a load of grain and head back to the ocean,” Rust said in an interview with the News Tribune.

Both 2019 and 2020 set records for the amount of wind energy components moved through the port,

and each year saw 85 total salties arrive (in 2020, 30 of those were for wind parts). But the number of salties arriving fell during the last two years, with 50 salties arriving in 2021 and 54 arriving through November of this year,

according to port statistics.

“So with the combination of fewer wind energy components coming in and the rates being high, the owners/operators of vessels say, ‘Why should I come in empty all the way to Duluth-Superior to pick up grain when I can make more money elsewhere?’ I think that’s the bottom line,” Rust said. “A lot of grain here to be exported, but it’s not going out by ship.”

Samantha Erkkila / File / Duluth News Tribune

Instead, grain is largely going out by rail, Rust said.

Unlike shipping’s tonnage reports, the amount of grain moved by rail is not public.

At the CHS, Inc. grain elevator in Superior, fewer salties were filled with grain this year.

Justin Cauley, senior director of transportation at CHS, said the war in Ukraine has disrupted demand. The country is one of the top exporters of grains like wheat, corn and barley.

Cauley said European demand for corn and beans shifted from the Black Sea to the Great Lakes, driving “much more” vessel demand in the Chicago and Toledo ports. If salties are discharging in lakes Michigan, Erie or Huron, then they are less likely to continue to Duluth and Superior, the western-most port on the Great Lakes, to fill up with grain.

“In ‘normal’ years, there are not enough cargoes in Chicago and Toledo to satisfy the number of inbound vessels. So, vessels were more willing to ballast to Duluth/Superior,” Cauley said in a statement to the News Tribune. “But until this, Ukraine grain supply comes back into play, we will most likely see empty vessels go to Chicago, Detroit and Toledo, rather than Duluth/Superior.”

Cauley said supply also played a role, noting that 2021 was a poor grain production year in North Dakota and Canada, but that “production is much better in the wheat belt this year.”

“Every year is different when it comes to grain, and every cent counts on a per-ton basis,” Deb DeLuca, executive director of the Duluth Seaway Port Authority, said in a statement. “It’s a very dynamic commodity in terms of supply, demand, pricing and routing. The world has seen two years of tightening grain supplies, further exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, and that coupled with the strong dollar, rising costs of transportation and competition from other countries’ less-expensive wheat makes for a challenging market.”

Like the Port of Duluth-Superior, the St. Lawrence Seaway, which connects the Great Lakes with the Atlantic Ocean, has seen a decline in grain shipments. Through November, 10.4% less grain has moved through the Seaway compared to the same time period last year,

according to the Seaway’s tonnage reports.

And it’s the lowest in five years, said Adam Tindall-Schlicht, administrator of the Great Lakes St. Lawrence Seaway Development Corp.

Jed Carlson / File / Superior Telegram

“I think what we are seeing is that Duluth’s export numbers have been really impacted by what has been a historically low wheat crop in the western prairies, including up into Canada,” Tindall-Schlicht said in an interview with the News Tribune. “And from our read, we believe that’s what maybe has contributed to a poor export year for grain through the Seaway overall.”

But he noted that other grains were doing well, pointing to beet pulp pellets. Through November, 139,635 short tons of beet pulp pellets had been exported from the port, a 72% increase compared to the same time period last year.

Still, there’s reason to be hopeful for a wheat comeback next year.

“The crop forecasters are looking to the western plains with optimism,” Tindall-Schlicht said. “And I think what we’re going to see is a nice little rebound from both U.S. and Canadian grain Seaway-wide tonnage increase, even early in the 2023 Seaway season.”

After all, fuel prices have come down and the U.S. dollar has weakened against other currencies — both just not soon enough.

“It was a case of too little, too late, in terms of those factors boosting waterborne grain movement from the Port of Duluth-Superior in 2022,” DeLuca said. “But if those improved conditions hold into 2023 — and the weather is conducive to another good crop — they could lead to a rebound.”

[ad_2]

Source link