[ad_1]

In this look at investment in the energy sector we examine the long-established, and by far the largest, segment – fossil fuels. Coal, oil and gas have been head and shoulders the largest providers of energy for domestic and industrial customers alike for more than a century; longer in the case of coal. However, these are ‘dirty’ businesses (in the context of renewable or alternative energy sources being ‘clean’) producing the materials that create the lion’s share of the world’s greenhouse gases. This creates many issues for ESG-led investment strategies.

This tag has long had an impact on equity valuations, with ‘dirty’ equating to low, often single digit profit multiples while ‘clean’ businesses, such as many technology stocks, run on sky-high valuations.

Show me the money

Big oil knows it is an industry with a shrinking future, even though forecasts suggest that neither oil nor natural gas demand is likely to drop in the next 15-20 years: in fact, both are forecast to grow – slowly but grow nonetheless. In the longer term, the pressures will become more acute as laggard nations such as China, India and the US (potentially worsening after the 2024 election) finally look to wean themselves off fossil fuels. The problem here for investors is the timescale. Most professional equity investors think at most five years ahead, equity markets perhaps only two years and many private investors more like six months, so investment and global ecological timeframes are massively misaligned.

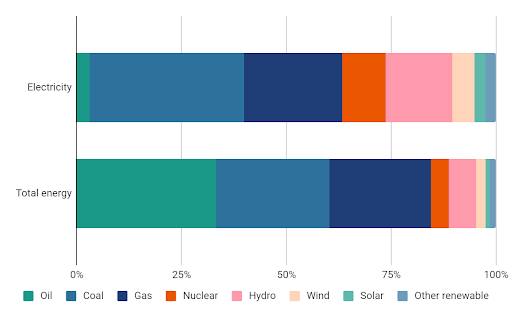

Global energy mix: electricity generation & total usage – 2021 TWh

Source: IEA, ourworldindata.org

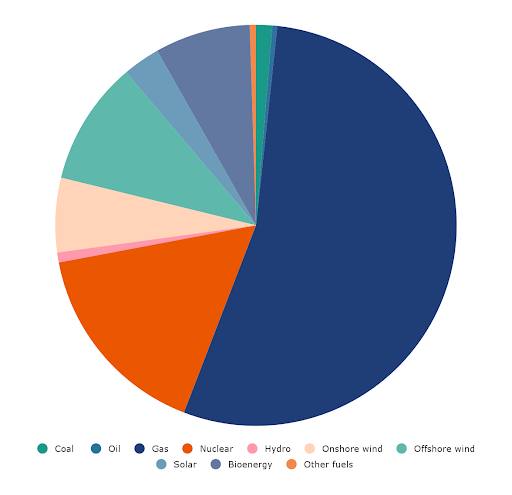

UK energy mix in electricity generation Q3 2022

Source: Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy

Big oil and gas – the integrated players

This is, by a huge margin, the largest investable portion of the energy market, hosting international and multinational companies. Oil companies (often oil and gas) such as Shell (SHEL), BP (BP.), Chevron (US:CVX), Total (FR:TTE) and Exxon (US:XOM) have revenues larger than many nations’ gross domestic product (GDP) and typically rank among the largest market capitalisations in their home stock markets. Shell’s earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (Ebitda) is larger than the GDP of 144 of the world’s national economies, and its market capitalisation is almost the same as New Zealand’s GDP.

The oil sector has been booming since the rebound from Covid-19 and the subsequent energy shock provided by the war in Ukraine, the Russian oil embargo, the perceived lack of slack capacity within Opec and poor output from the shale industry in the US. But oil prices are predicted to fall, with Peel Hunt forecasting $90, $80 then $65 in 2023-25 for Brent crude. Does this mean that oil stocks are set to fall by one-third in line with the oil price? Despite a high historic correlation, probably not because the super-normal profits now being made are ‘price/earnings (PE) of 1x’, reflecting their windfall nature, so losing those additional earnings over time should not drag on ratings. After such strong rallies in the past year, a pause for breath feels inevitable, but with rationalisation, heavy cost cutting, the benefit of large share buybacks, the lessening threat of surtaxes as the oil price drops and the hoped-for stronger push into cleaner energy by big oil (they have massive resources to invest) valuations could find some support.

Above we refer to the sizable risk to the large energy companies from ‘windfall’ taxation, a surcharge on what governments believe to be excess profits generated from rising oil and gas prices. Taxing these excess or unexpected profits is seen by many as a ‘victimless’ intervention as the companies had not expected the gain so wouldn’t miss it if it was taken away. This viewpoint is underscored by the decisions to undertake large share buybacks rather than invest the gains. However, this is not a level playing field, and taxing windfall in the UK if the US, Saudi Arabia, Russia or Canada do not, means those taxed are disadvantaged. A better way might be to tax very heavily the share of profits not reinvested in clean energy. The incentive for the oil company would be new and highly rated profit streams.

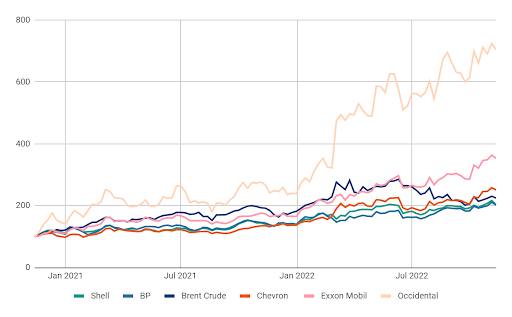

To some extent (and certainly in the past two years), big oil stocks have largely been a proxy for the oil price, especially Shell and BP, and as our chart shows there is almost nothing to pick between the two UK oil majors. The US stocks have done better and Warren Buffett’s reported favourites Chevron and Occidental (US:OXY) have outperformed. So, for stockpicking: bias to the UK, but just flip a coin between the two giants and tread carefully in the US as it looks a little overbought.

Big oil share prices and the oil price: Index = 100 Nov 2020

Source: Factset

Just gas

The bulk of the world’s natural gas is a by-product of oil extraction and it is harder to find pure-play gas businesses, but they can be found in the US in stocks such as CNX (US:CNX) or Southwestern Energy (US:SWN), but these tend to be exceptionally volatile.

Another part of the gas industry that has become much more visible in Europe since the conflict in Ukraine is liquified natural gas (LNG). This is gas shipped by sea rather than pipelines, thus offering flexibility in end markets. However, the volumes that can be carried even on tanker-sized vessels, even with compression ratios of 1:600 mean a typical shipload of 150,000m3 in liquid form is only enough per load to provide c40 per cent of a day’s consumption in the UK.

Most of the world’s LNG is controlled by state-owned oil companies and in the listed sector is dominated by Shell and Total, however, there is one dedicated stock – Cheniere Inc. (US:LNG). This has been a boom stock, benefiting from the global disruption of supply due to Russia’s interventions.

There is a mantra that we will never achieve net zero while the world is burning gas – perhaps why National Grid (NG) recently sold off its gas business: good profits but a millstone for the rating. But the largest use globally for natural gas (around 60 per cent) is in the production of hydrogen for making ammonia, then fertiliser. The dominant process is ‘steam reformation’ or ‘grey’ hydrogen and while cleaner ‘blue’ and ‘green’ hydrogen processes exist they remain at a very small scale and require enormous capital investment to become dominant. Gas demand looks pretty stable.

King coal’s reign over?

In most economies, coal is being edged out of the energy mix, but it remains a large industry. In the UK, coal accounts for only around 2 per cent of electricity generation and is largely banned for domestic use. But it has enjoyed a brief respite due to the UK’s energy gap (caused by nuclear decommissioning and a lack of wind in 2021) but the direction of travel is towards elimination. There are, essentially, no routes to coal investment in the UK, but other nations (especially the US, China and large extracting nations such as Poland) do offer opportunities. Global coal extraction remains high and investors’ best access, should they wish to invest in the dirtiest of fuels, is via large international general mining stocks such as Peabody (US:BTU) or BHP (AU:BHP).

Smaller oil – the E&P sector still offers high risk/reward profiles

While the bulk of the market value in the oil and gas sector is found within the larger oil stocks, the greatest number of stocks are found in the large and sprawling exploration and production (E&P) sector. These are upstream businesses discovering and extracting oil to sell on into the wholesale market, from where pure refinery or large oil companies convert the crude oil. This sector has a vast array of business sizes from FTSE 350 stocks such as Capricorn Energy (CNE) with an £800mn market cap producing 35,000 barrels a day, down to small Aim-traded stocks such as Union Jack Oil (UJP) – market value £36mn – where output is just a couple of hundred barrels a day. Global production is 90mn barrels a day. In the US, there are some giant E&P oil businesses, the largest being ConocoPhillips (US:COP), currently valued at $48bn.

In this sector, investment is more speculative if looking at the smaller end, with stocks focused on small, local markets or running small portfolios. The bulk of the sector contains integrated stocks that explore, discover, develop and operate oil production. There are a handful of pure exploration stocks but these are ultra high-risk, do-or-die businesses. So while big oil, in more normal times (assuming we ever see those again), is the steady and ‘safe’ performer that will give long-term, mid-single-digit total shareholder returns (TSR), the big returns are more likely to come from E&P in the long term. On literally striking oil, an E&P stock can rise by a huge percentage.

When investing in the big oil companies, it is easier to see how global swings in demand and oil price are likely to drive equity valuations, but the much narrower focus of most E&P stocks leans much more on micro-specifics. For example, Rockhopper (RKH) relies on success in the Falkland Islands and the unlikely Italian extraction market; Savannah (SAV) is all about the markets in Chad and Cameroon. Essentially, for many stocks in this sector, other than the giant US E&Ps, investors will need to do a lot of homework before investing – this is not a simple play on global trends. This very narrow focus also means that timescales before seeing positive outcomes can be very long and the often ‘jam tomorrow’ nature of this sector has led to a great deal of investor exhaustion. Many general fund managers have in recent years tended to steer a wide berth for just that reason.

This narrow focus and the often more speculative nature of production also mean that valuations can be difficult. Each asset needs to be risk assessed/adjusted, local trading or political climates accounted for, many valuations rely on very long discounted cash flows (DCF) and complex sum-of-the-parts valuations. These factors can be pretty opaque to private investors and traditional metrics (PE, EV/Ebitda or price/book) do not readily stack up.

So, should investors avoid the E&P sub-sector? No, but only dive in after plenty of research, adopting a robust attitude to risk and taking a portfolio approach – single-stock speculation can be akin to investing in crypto. That said, the E&P sector appears to be on a more solid financial footing than historically was the case, there are more dividends or share buybacks being paid out and there is a high level of corporate activity. There is also a rationalisation of still high-quality assets under way by the big oil businesses, which is allowing many E&P businesses to enhance their portfolios and/or de-risk by increasing diversity. All told, the prospects for the sector’s larger players look good and there is an interesting new dimension of potential takeovers for the better small entities. Despite this, the Aim oil and gas sector has fallen sharply in the past year, reflecting the greater likely impact from a slowing global economy, but this has may also have created pockets of value, albeit pregnant with risk.

Investors should stick towards the larger end when looking at UK E&P, with stocks such as Savannah (£300m), Touchstone (TXP:£155mn), Diversified Energy (DEC:£1.1bn) or Jadestone (JSE:£350mn). For more excitement and risk, at the smaller end perhaps Union Jack Oil or one of the few exploration-heavy stocks, Deltic (DELT:£63mn).

[ad_2]

Source link