[ad_1]

The billions of tons of cement made each year have an enormous carbon footprint: 8% of global emissions, or four times more than the airline industry. That’s both because of the energy used to make cement—a process that involves heating up crushed rocks to as much as 2,800 degrees Fahrenheit—and because limestone, the main material, also releases CO2 directly when it’s heated. (Limestone is made mostly from calcium carbonate, and breaks down into lime, used in cement, and carbon dioxide.)

A growing number of startups are racing to make alternatives, including “biocement” made with microbes, concrete that can capture CO2 to help offset the emissions from making cement, and cement that replaces limestone with other rocks that don’t create the same emissions. A startup called Terra CO2 is in the latter group, and argues that it can scale up more quickly than its competitors because it uses accessible, cheap materials. The company announced today that it raised $46 million in a Series A round of funding led by Breakthrough Energy Ventures, the climate-focused VC firm launched by Bill Gates, and LENX, the investment arm of Lennar, one of the largest construction companies in the U.S.

The startup’s process partly replaces Portland cement, the limestone-based “glue” in concrete, with silicate rocks that are dug up in aggregate mines, which are already in operation all over the country. “Concrete is so massive, if you don’t have a scalable, raw material that you could pretty much get anywhere, you’re not gonna move the needle a lot,” says Bill Yearsley, Terra’s CO2, who spent 40 years in the construction materials industry before cofounding the startup. “And we are working with silicate rock types, which is the most abundant rock on the crust of the earth.”

About seven years ago, Yearsley partnered with D.J. Lake, a materials scientist who had been working on a cement alternative that spun out of university research. “We soon saw that this had potential to reduce CO2 emissions in a huge way,” Lake says. After grinding up rocks, the technique involves heating them in a way that creates essentially a powder of tiny glass spheres. The material, known in the industry as a type of “supplementary cementitious material” or SCM, can help partially replace cement.

It plays the same role as fly ash, a waste product from coal manufacturing that is also used in concrete to partially replace cement. But as coal plants have closed, less fly ash is available—and, of course, burning coal isn’t compatible with climate goals. If Terra’s material is made with clean energy, it can have zero emissions. “We are technically able to produce a carbon neutral manufactured SCM today, however, our constraint is economics,” Yearsley says. Right now, the company can’t use renewable hydrogen or electricity and compete on costs, but it expects to eliminate emissions over the next five years.

To scale up quickly, he says, a low cost is necessary. “All of our products are cost competitive with the incumbents and that’s before any kind of green or government incentives like carbon credits,” he says. “We don’t model any of that stuff in. We of course apply for it all like everybody else does, but we’re cost competitive without that.” The product also works within the existing infrastructure in the concrete industry, so concrete plants don’t have to make any changes, just swap in the new material. The product has gone through third-party testing to show that it performs as well or better than alternatives.

Because the concrete companies also have mines producing the rocks that Terra needs, the startup will also be a customer, increasing the incentive for concrete companies to make the switch. “In most cases, we can use the lowest value of material coming out of their mines, the cheapest stuff, which makes their life easier,” says Yearsley. “And then we produce this [product] and we can sell that to them and they can turn around and use it in their own ready mix concrete plant.”

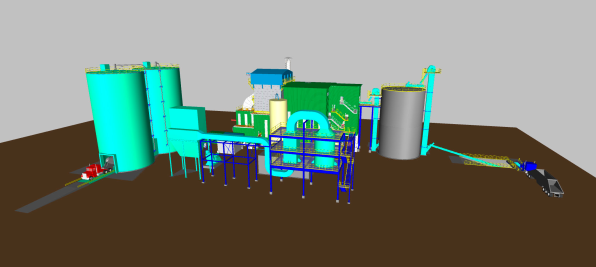

Terra is running two small pilot plants today, and its first commercial plant will break ground in Denver next year, capable of supplying around half of the supplementary cementitious material used in the metro area. More plants in other cities will follow. The first product will be used to replace 10-30% of the cement in concrete. If half of the concrete industry in the U.S. made the switch, replacing 20% of the cement in their blends, the company estimates that it could save nearly six million metric tons of emissions each year. Another product that will replace 50% of cement will follow.

The company is also working on the bigger challenge of completely replacing Portland cement with other low-cost materials that can bind concrete together. These new materials are a few years from commercialization, Yearsley says. “We want the resulting concrete to look, feel, and perform just like familiar everyday concrete,” he says. “The goal is to swap out the cement component, lower the environmental impact, and still use all the same mixing equipment, trucks and infrastructure used by concrete today.”

[ad_2]

Source link